Liner notes from original albums and CDs for proofreading

Ever feel that the daily grind of making a living was interfering with living itself? Tired of big business deals, mass culture, bomb shelters? Then come for an exciting subway ride with composer Jule Styne and arranger-conductor Percy Faith. Percy is an expert guide through Jule Styne’s irresistible score for the new Broadway musical hit, Subways Are for Sleeping, all about Manhattan’s zany “underground” population. Book and lyrics are by the famed team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

Percy Faith’s arrangement of the opening number begins, appropriately, with drums representing the distant rumble of a subway train, then swells to a roaring orchestral crescendo as we Ride Through The Night to meet some of New York’s most relaxed and picturesque odd-balls. The easy-going strains of I’m Just Taking My Time puts us in a receptive mood to meet these carefree denizens of subways, Grand Central Station benches—and even deserted galleries in the hallowed Metropolitan Museum of Art! We discover with them how amicable the world really can be as we listen to the cheerful, lilting When You Help a Friend Out.

Who Knows What Might Have Been? Introduces us to the show’s hero Tom Bailey, ex-business tycoon turned odd-jobber (walking people’s dogs is a specialty). A chance encounter in the subway introduces him to a runaway bride, Angie McKay. The driving tempo of Getting Married reflects Angie’s impetuous decision to escape matrimony with her boss for whom she represents a combination tax deduction and social hostess.

Percy Faith emphasizes restless, insistent percussion and wistful strings in his arrangement of I Just Can’t Wait. (Charlie Smith, professional meal moocher, can’t wait for the treat of seeing his girl friend fully dressed—her “system” is to wear a wrap-around bath towel in her hotel room and thus for long, rent-overdue periods stave off forcible eviction!)

Tom avoid the Christmas gift rush by standing still—as a street corner Santa Claus, collecting money for the Community Center. Percy Faith lends the spirited, joyous Be A Santa a rousing orchestral treatment. Sleigh bells jingle gaily, church bells ring out merrily and piccolos tweet brightly in this captivating salute to the Yuletide.

Percy’s famous trademark, silken strings, are used appropriately for How Can You Describe a Face?, Tom’s eloquent attempt to describe Angie’s beauty. Now I Have Someone is equally persuasive.

Come Once in a Lifetime is a characteristically-buoyant Jule Styne showstopper. Conductor Faith captures brilliantly its infectious exuberance. Wind instruments followed by rhapsodic strings translate into purely orchestral terms Angie’s declaration of love, I Said It and I’m Glad.

Percy Faith concludes his musical tour of the Subways system by answering the happy question, What Is This Feeling in the Air? With a hint of wedding bells.

—CURTIS F. BROWN

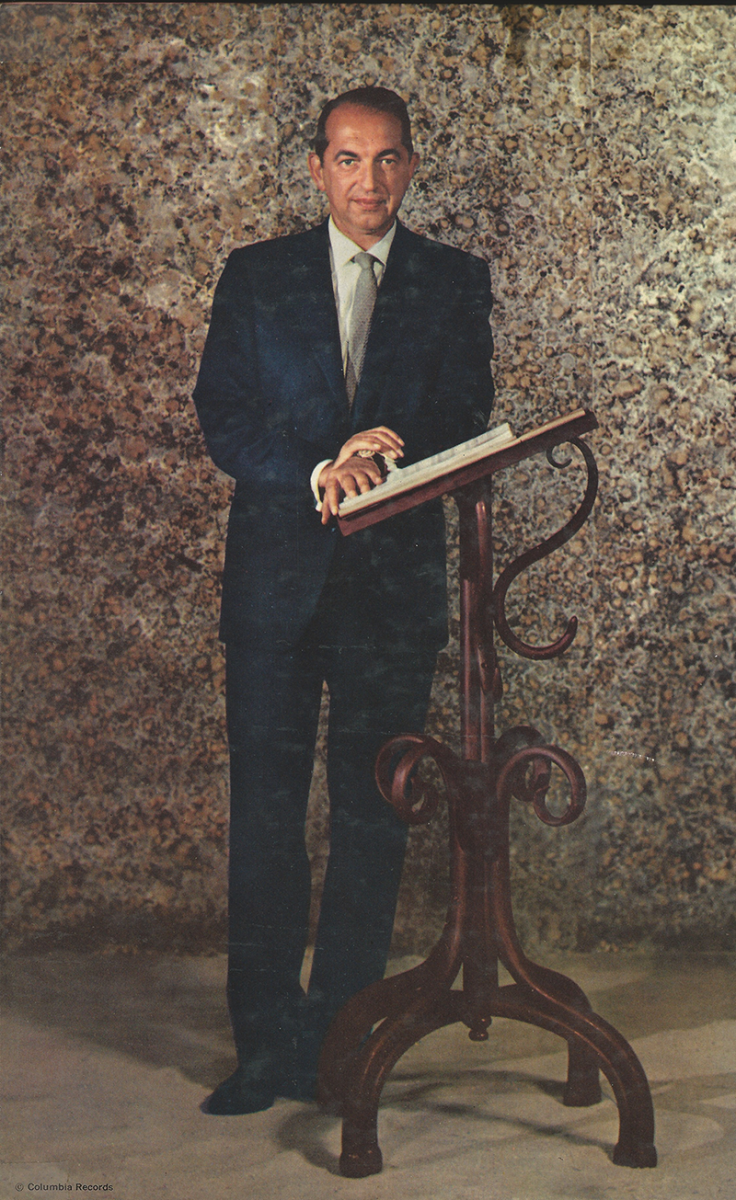

Percy Faith, composer-arranger-conductor of international fame, has accumulated a long, impressive list of successes and awards. His recording of The Song from “Moulin Rouge” won the “best-selling single of the year” award from Cash Box, the show business magazine. His arrangements of Because of You; Cold, Cold Heart and Rags to Riches helped Tony Bennett win three gold discs for sales topping the million mark. An original song, My Heart Cries for You, also sold over a million discs and was instrumental in launching Guy Mitchell’s career as a major recording artist.

In 1955 Percy Faith received an Academy Award nomination for scoring and conducting the musical sound track for the movie Love Me or Leave Me. An expert arranger for such top vocal stars as Rosemary Clooney, Johnny Mathis and Doris Day, Percy’s album collections range from Latin American rhythms through mood music to immensely popular orchestral settings of Broadway shows, including Kismet, My Fair Lady, Porgy and Bess, The Sound of Music and Camelot.

The suave arrangements of Percy Faith have propelled three superb records over the million-seller mark: Theme from “A Summer Place,” “The Song from Moulin Rouge” and “Delicado.” Moreover, it was Percy himself who adapted “The Song from Moulin Rouge” from the original movie score, and whose music for “My Heart Cries for You” provided singer Guy Mitchell with his first million-selling record. This collection of great themes from motion pictures, including Percy’s latest composition, the theme from “Tammy Tell Me True,” is in the same great Faith tradition, sumptuous, tasteful and exciting. Percy Faith was born in Toronto, Canada, on April 7, 1908. He began his studies early, and worked so studiously that by the time he was eleven, he was earning three dollars a night (plus carfare) as a pianist for silent movies in a Toronto theatre. At fifteen, Percy made his concert debut as a pianist in Massey Hall. As he continued his studies, he discovered a growing interest in arranging and composing, which in time outran his desire for a pianistic career. In 1933, he was appointed staff conductor for the Canadian Broadcasting System, where he remained until 1940 when he moved to the United States to become conductor of “The Contented Hour.” In 1947, Percy became conductor of “The Pause That Refreshes on the Air,” later for “The Woolworth Hour.” Other radio programs and guest appearances with such orchestras as the NBC Symphony further enhanced his reputation. He joined Columbia Records in 1950. Conservatory-trained Faith follows a composer’s intentions so sympathetically that he never distorts a melody. He enhances it, adding exotic color with instruments, creating constant surprises with counterpoint of tunes or intricate rhythms. His inventions are so considerable that a Percy Faith arrangement can be virtually a fresh composition, yet it never masks the original. The sound of his massed violins, his lustrous brasses and his impeccable tempos is unmistakable.

Rock ‘n’ roll is generally presumed to be a young person’s game, so it may come as a surprise to learn that the best-selling instrumental of the rock era was a lush, richly orchestrated ballad credited to a 52-year-old conductor. Percy Faith was the conductor and his hit was The Theme From “A Summer Place.” It sold well over a million copies and topped the Bilbaord pop chart for nine weeks in early 1960.

Born in Toronto, Canada, April 7, 1908, Faith learned to play the violin by the time he was 7. He went on to study at the Toronto Conservatory of Music. He also played piano in a silent movie theater and the violin with several Canadian orchestras.

When Faith was 18 he severely damaged his hands trying to put out a fire at a clothing store operated by his sister. His violin-playing days were over but he continued in music, working as a conductor and arranger, joining the Canadian Broadcasting Company in 1933. He had his own show – “Music By Faith” – that was so popular in Canada it was picked up for broadcast in the U.S. by the Mutual Broadcasting System.

Faith relocated to the United States in 1940 as musical director for a radio series called “The Carnation Contented Hour.” In 1950, he was hired by Columbia Records’ head Mitch Miler to serve as an arranger and conductor for the label’s staff orchestra.

The Faith touch was soon heard on huge pop hits for Tony Bennett, including Because Of You (1950), Cold Cold Heart (1952) and Rags To Riches (1953). Faith also worked on big singles for Guy Mitchell, Rosemary Clooney, Frankie Laine and Doris Day.

Miller also encouraged Faith to record on his own and his first success came in 1950 when I Cross My Fingers, with a vocal by Russ Emery, was a Top 20 hit. All My Love, also issued in 1950, went Top 10. Faith closed out the year with Christmas In Killarney, which was a Top 30 song.

The hits kept coming in the early ‘50s. In 1951, he went Top 10 with On Top Of Old Smokey which sported the voice of Burl Ives. He also did well with When The Saints Go Marching In. Delicado, issued in the spring of 1952, went to No. 1 for a week.

In the spring of 1953, Faith’s recording of Swedish Rhapsody went on the charts where it would peak at No. 21. It’s flip side, Song From ‘Moulin Rouge’ (Where Is Your Heart), with a sweet vocal by Felicia Sanders, went on the Billboard list a month after Swedish Rhapsody. It would stay there for 24 weeks – 10 at No. 1 – and be cited as the best-selling record of 1953.

Later in ’53 Faith had a Top 20 record with Return To Paradise. Many Times was also popular that year. In 1954 he charted with Dream, Dream, Dream and The Bandit.

While Faith’s singles were being challenged by Elvis Presley and his pals, the conductor was doing well on the album charts. Adults were taken with his lush arrangements of standards and “Passport To Romance” was a Top 20 in the summer of 1956. “My Fair Lady,” with songs from the enormously popular Broadway musical, did even better, going Top 10 in 1957. A collection of songs from “Porgy And Bess” did well in 1959. In 1960, both “Bouquet” and “Jealousy” were Top 10 sellers.

In the early fall of 1959, Faith – who continued to release an occasional single – recorded the them from Warner Bros.’ “A Summer Place.” It was a steamy story of young love starring teen sensations Sandra Dee and Troy Donahue and adults Dorothy McGuire, Richard Egan and Arthur Kennedy. The single took almost six months to edge into Billboard’s Hot 100 in January 1960.

Once it got on the charts, the record moved quickly, and, after less than two months, it settled in at the top of the rankings for a nine-week run. It also won a Grammy as Record of the Year.

Despite his massive hit, Faith didn’t release an album based on the single. But he didn’t seem to need to as his albums of lush mood music continued to sell very well. In 1961, he was back in the Top 10 with music from “Camelot.” That was followed by popular collections featuring the music of Mexico and Brazil.

In 1963, Faith slightly altered his musical direction. He was still doing lush collections of instrumentals, but he switched from standards as his source to the Top 40. “Themes For Young Lovers” featured his 1960 hit of the same name and string-filled arrangements of teen hits like Go Away Little Girl, All Alone Am I and On Broadway. The sparkling sound of the album pushed it to Billboard’s Top 15 and eventual gold record status.

Faith continued to offer his versions of pop hits on “Shangri-La” and “Great Folk Themes.” In 1964, he was back with “More Themes For Young Lovers.”

Through the early ‘70s, Faith continued to record popular albums featuring his orchestra and chorus, including “Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet,” for which he received a 1969 Grammy for Best Contemporary Performance by a Chorus.

In all, Faith had 30 albums on the Billboard charts between 1956 and 1972. Three of them went gold.

Faith died of cancer February 9, 1976. He left a huge legacy of great music during his years on Columbia and Collectables is pleased to present some of the best of that work on this tribute to a man who spent more than 40 years bringing fine music to the work.

– Mark Marymount

The Percy Faith Strings, born a dozen years ago in a golden and inevitable album we called Bouquet, are, indeed, the essence of the Percy Faith writing. In four wedges of first and second violins, violas and cellos, forty-eight of the finest string players in the world spread out from the podium like four exquisite ribs in a delicate fan of sound—a Beatle ballad as familiar as a friend woven into counter melodies so precisely right that they too sound familiar. Then, the startling individuality of a flugel horn, an alto sax, a trombone or a flute appears warm and confidential, then disappears again into the flowing strings. Percy Faith, the composer, the arranger, the conductor, distills in this orchestra these complimentary talents, which, for him, are best expressed by the bows of a family of strings.

The songs of The Beatles, which “play for strings” was the criterion. The most memorable and meaningful compositions of the past decade of important music are the program. To some these performances simply reinforce what they have always known—that these songs are beautiful. To some others this new and flattering expression of the songs brings, at last the new realization. To me, and probably to you, the setting fits the gem, and the listening is lovely.

And isn’t it nice to know that not everything in the air waters the eyes, stings the membranes, shatters the atmosphere? This graceful, airborne music enhances our environment and charms the surface of the earth just as Thoreau’s flute, floating above Walden, charmed the perch in the pond.

Irving Townsend

The four creative minds of The Beatles (John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr) and “Jesus Christ Superstar’s” two originators (Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice) are unanimously considered by both musicologists and casual listeners as among the very best composers of the last 50 years. Their music has been, to this day, the soundtrack of our lives. They are continually paid homage by other artists who record interpretations of their music.

In 1970 and 1971, one of Columbia Records’ most prolific and popular musicmakers, orchestra leader Percy Faith, produced two projects, “The Beatles Album” and “Jesus Christ Superstar” that reflected the public’s fascination with the two, and the joy their music brought to millions.

Since 1950, when he arrived at Columbia as both a recording artist and music director, the Toronto-born Faith began producing albums of tunes that were linked either conceptually, lyrically, or through association with a specific artist, project or part of the world. Albums like “Viva! The Music Of Mexico,” released in 1958, and “The Sound Of Music,” a 1960 issue, focused on their subjects to great effect, achieving commercial success. Faith would utilize the formula of translating well-known melodies into fantastically ornate and richly wrought orchestral works of dynamic beauty. His distinctive voicings for strings and innovative recording techniques made him the undisputed leader in the field of recorded instrumental music. He treated pop with the dignity of classical music, and made records that have withstood the test of time.

What can be said about the Beatles that has not been already said by hundreds of writers? No one alive during their time will ever forget them. Their songs combine romance with fancifully imaginative concepts in a refreshing innocence that is at once strange, yet completely memorable. Combine with a joie de vivre that was a trademark of the Sixties, and you have music that resides at pop’s pinnacle.

The delight of surprise abounds in Beatles music, and “The Beatles Album” is full of creative interpretations of their music. The pizzicato strings of Eleanor Rigby, the quiet grace of Because, which is based on Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata played in reverse, and the unlikely choice of The Ballad Of John And Yoko, one of the group’s more controversial tunes, are highlights. The musical contributions of Ted Nash on saxophone and Buddy Childers on flugelhorn should not go unnoticed, as they excel in their solo spots.

As the son of William Lloyd Webber, the director of the London College Of Music, Andrew Lloyd Webber was exposed to “good” music at a tender age. He would later train at the Royal Academy Of Music, an unlikely place for a “pop” songwriter to begin his career.

In the 1970s, “concept” albums were in vogue. A record album was a relatively inexpensive way to stage a musical. His first effort, “Joseph and The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,” received critical kudos but at the time remained unproduced. The second attempt to write a musical by Webber and lyricist Tim Rice was a world-wide ground-shaking event. “Jesus Christ Superstar,” released in 1971 first as a full-length recording project, had all the right elements. A fresh, melodic score with the brash swagger of great rock music made the piece a natural for theatrical production, as well as being based on the most famous “book” and lead character in history.

The musical “Jesus Christ Superstar” re-energized Broadway, and paved the way for later Andrew Lloyd Webber masterpieces like “Evita,” “Cats,” “Phantom Of The Opera,” “Aspects Of Love,” and “Sunset Boulevard.” Andrew Lloyd Webber is today the reigning monarch of the musical.

His “Jesus Christ Superstar” partner, Time Rice, has also fared well in the theatre. Besides their collaboration on “Evita,” Rice has the album / musical “Chess,” written in collaboration with Abba’s Bjorn and Benny, and his recent work with Elton John (“The Lion King,” “Aida,” and “The Road To El Dorado”) as evidence of his outstanding contribution to the history of Broadway and the film musical.

In the capable hands of a master like Percy Faith, the music of The Beatles and Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice is meticulously presented. They are our modern-day Schubert and Gershwin, creating popular songs for the ages. Here now are two landmark examples of their brilliant careers, “The Beatles Album” and “Jesus Christ Superstar.”

— Al Fichera

1991 compilation

The music of George Gershwin played in this collection by Percy Faith and His Orchestra is discussed here chronologically, to help place it in perspective.

Somebody Loves Me

This song was unforgettably interpreted by Winnie Lightner in the Scandals of 1924. Its appeal is primarily melodic, for in this song Gershwin tapped the rich, full-blooded lyricism that henceforth would identify his best love songs. Gershwin’s way of suddenly interpolating a flatted third in the melody here personalized his writing. The nebulous harmony was also a part of the song’s charm. “Somebody Loves Me” was one of Gershwin’s greatest hits after “Swanee.”

Oh, Lady Be Good and Fascinatin’ Rhythm

Lady Be Good was Gershwin’s first major musical-comedy success. It opened on December 1, 1924, the first musical produced by the new team of Aarons and Freedley, who were to be associated with so many Gershwin musicals. Fred and Adele Astaire were starred. Cast as a brother-and-sister dancing act who had come upon unhappy days.

Gershwin’s music was the principal attraction of this gay musical. Never before had he brought such a wealth of original invention to his stage music. The irresistible appeal the repeated triplets in the title song, the kinesthetic effect of the changing meters in “Fascinatin’ Rhythm”—all this represented a new sophistication in popular music.

The Man I Love

The best song Gershwin wrote for Lady Be Good was not in the show when it opened in New York. It has since become one of the Gershwin song classics, and the one song he often considered his greatest. But before it finally achieved recognition it had an eventful history. The chorus as it is known today originated as the verse for another song; but Gershwin soon realized that the individual melody consisted of a six-note blues progression that reappeared through with cumulative effect, achieving poignancy through the contrapuntal background of a descending chromatic scale. In rewriting his song, Gershwin now used the verse as the chorus, and prefaced it with a simple but appealing introductory tune.

“The Man I Love” was sung by Adele Astaire in the opening scene of the Philadelphia tryout of Lady Be Good. In that setting the song missed aim completely; it was too static. Vinton Freedley insisted that it be dropped from the show, and Gershwin consented. In 1927, Gershwin removed the song from his shelf and incorporated it into the score he was then writing for Strike Up the Band (first version). Once again it was tried out of town, was found wanting, and was deleted.

But the song found admirers. One of them was Otto H. Kahn, to whom Gershwin played it when he planned using it for Lady Be Good. Kahn liked the song so much that he decided to invest $10,000 in the musical. Another admirer was Lady Louis Mountbatten, to whom Gershwin presented an autographed copy in New York. When she returned to London, Lady Mountbatten arranged for the Berkeley Square Orchestra to introduce the song there. It became such a success that—though no printed copies were available in England—it was picked up by many other jazz groups in Paris, where it also caught on. American visitors to London and Paris heard the song and, returning home, asked for it. Then singers and orchestras took it up until its acceptance in this country became complete.

Gershwin has explained that the reason it took so long for the song to be appreciated is that the melody of the chorus, with its chromatic pitfalls, was not easy to catch; also, when caught, it was not easy to sing or whistle or hum without a piano accompaniment.

Preludes Two and Three

On December 4, 1926, at the Hotel Roosevelt in New York, Marguerite d’Alvarez, the operatic contralto, gave a serious song recital that included French and Spanish art songs. Gershwin participated, not only by accompanying her in his songs, but also by appearing as piano soloist. On this occasion, he gave the world premiere of his Preludes for the piano.

The second, in C-sharp minor (Andante con moto e poco rubato) is the most famous of the set: a poignant three-part blues melody set against an exciting harmony that grows richer as the melody unfolds. Rhythm once again predominates in the third prelude, in B-flat major (Allegretto ben ritmatto e deciso), an uninhibited outburst of joyous feeling.

Clap Yo’ Hands, Maybe, and Someone to Watch over Me

Oh, Kay, in 1926, was the first American musical comedy starring Gertrude Lawrence, who had made her Broadway debut in 1924 in the Charlot’s Revue imported from London. When Aarons and Freedley discussed with her the possibility of coming to New York in a new musical, she was considering a similar offer from Ziegfeld. The information that George Gershwin would write the music was the deciding factor in her acceptance of the Aarons and Freedley contract.

The Gershwin score was a rich cache of treasures, “a marvel of its kind,” as Percy Hammond Reported. To no other musical production up to this time had he been so lavish in his gifts. There was “Someone to Watch over Me,” in his most soaring and beguiling lyric vein touched with the glow of Gertrude Lawrence’s charm, “Clap Yo’ Hands,” with its fascinating rhythms, and “Maybe.”

‘S Wonderful

In 1927, Aarons and Freedley built a new theater for their productions, the Alvin on West 52nd Street. It was a house that Gershwin had helped build with the profits from Lady Be Good, Tip Toes and Oh, Kay. What, then was more appropriate than that it should be opened on November 22 with a new Gershwin musical? The musical was Funny Face, in which Fred and Adele Astaire made their first welcome return in a Gershwin musical since Lady Be Good. Victor Moore was also in the cast, appearing as a helpless, hapless thug who gets involved in all sorts of difficulties while trying to steal a string of pearls. “’S Wonderful” was the hit of the show.

Liza

“Liza” was a particular favorite of Gershwin’s. He continually played it for friends, frequently with improvised variations. It appeared in Show Girl, a lavish Ziegfeld production, in 1929. Ruby Keeler sang and danced to its tantalizing rhythms, as her husband Al Jolson ran up and down the aisles singing the refrain to his wife—for several nights an unscheduled, unexpected and unpaid-for attraction.

Soon

With Strike Up the Band, in 1929, a new kind of musical came to Times Square. This was no longer just a spectacular for the eye and an opiate for the senses—as had been the case with so many earlier Gershwin musicals—but a bitter satire on war, enlisting all the resources of good theatre….It was first launched in 1927…and was abandoned. In 1929, the authors returned to the play….It brought new dimensions to musical comedy by being one of the first with a pronounced political consciousness.

The Gershwin score—which was published in its entirety—is not only rich in details. Individual songs stand out prominently, “Soon” is one of Gershwin’s most beautiful ballads, unforgettable for its purple mood.

Embraceable You, Bidin’ My Time, I Got Rhythm

Girl Crazy, one of Gershwin’s greatest musical-comedy successes, began a long run at the Alvin Theatre on October 14, 1930. The book, by Bolton and MacGowan, was no better—and no worse—than earlier ones for which Gershwin supplied the music….One of the things that made Girl Crazy as good as it was—“a never-ending bubbling of pure joyousness,” as one New York critic described it—was the casting. Ginger Rogers, fresh from her first screen triumph in Young Man of Manhattan, here made her bow on the Broadway stage. Willie Howard brought his accent and uninhibited comedy to the part of Gieber Goldfarb. Allen Kearns, veteran of many Gershwin musicals, was cast in the male lead. Each of these gave a performance calculated to steal the limelight. But the limelight belonged not to any of them, but to a young and then still unknown lady whose personality swept through the theater like a tropical cyclone, and whose large, brassy voice struck the consciousness of the listeners like a sledge hammer. She was Ethel Merman, in her first appearance in musical comedy….In “I Got Rhythm” she threw her voice across the footlights the way Louis Armstrong does the tones of a trumpet. When, in the second chorus, she held a high C for sixteen bars, while the orchestra continued with the melody, the theater was hers: not only the Alvin theatre, but the musical theater as well. “I Got Rhythm” is remarkable in its chorus not only for the agility of the changing rhythms, but also for the unusual melody made up of a rising and falling five-note phrase in the pentatonic scale.

“Embraceable You,” the hit song of the production, belongs to the half dozen or so of Gershwin song classics in which his melodic writing is most expressive.

Mine

In 1933, many of those who had helped make the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Of Thee I Sing” the historic occasion it was in the theater, joined forces for a sequel entitled Let ‘Em Eat Cake….There was much that was bright and witty and stinging; but the play as a whole did not quite jell. The critics and audiences rejected the play and it failed to reach its hundredth performance on Broadway.

On the positive side was one of Gershwin’s important songs, “Mine.” This was a pioneer attempt to use a vocal counterpoint for the main melody (a practice subsequently employed so effectively by Frank Loesser in “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” and Irving Berlin in “You’re Just in Love”). The vocal counterpoint consists in an aside by the chorus which carries overtones of Gilbert and Sullivan.

I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’, Summertime, Bess, you Is My Woman Now, My Man’s Gone Now

The writing of Porgy and Bess occupied Gershwin for about twenty months. Most of the actual composition was done in about eleven months and completed in mid-April 1935. While some of the orchestration for the first act had been done in September 1934, that task consumed about eight months in 1935. Then it was completed: seven hundred neat and compact pages of written music (560 pages of the published vocal score), which if performed as written would require four and a half hours. During rehearsals, cuts had to be made in order to compress the opera within the prescribed limits of a normal evening at the theater.

Porgy and Bess opened at the Colonial Theatre in Boston on September 30, 1935. The audience began early to demonstrate its enthusiasm, and by the time the opera ended the ovation reached such proportions that the shouts and cries lasted over fifteen minutes….Two weeks later, on the evening of October 10, Porgy and Bess came to New York, to the Alvin Theatre….

They Can’t Take That Away from Me, They All Laughed, A Foggy Day, Nice Work if You Can Get it, Love Is Here to Stay, Love Walked in

After 1935, and up to the time of his death, Gershwin worked exclusively for motion pictures. His first film, during this period, was a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musical, Shall We Dance?, described by The New York Times as “One of the best things the screen’s premiere dance team has done, a zestful, prancing, sophisticated musical.” Gershwin’s score was a gold mine, and two of the treasures were the deft and suave “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” and “They All Laughed.”

One chore completed, Gershwin went to work for another screen musical. The star once again was Fred Astaire, but this time he was paired with a new dancing partner, Joan Fontaine. This film, A Damsel in Distress, would not have been “half so good without the splendid Gershwin melodies,” reported Howard Barnes in the New York Herald Tribune. The best of these melodies were “A Foggy Day” and “Nice Work if You Can Get It.”

Gershwin’s last score was for the Goldwyn Follies, for which he did not live to complete. He was able to write only five numbers for that production, and for some of those Vernon Duke had to provided the verses. Since two of these Gershwin songs are among his most beautiful—“Love Is Here to Stay” and “Love Walked in”—it is apparent that even in his last troublesome months there was no creative disintegration, and that when he died so prematurely he was still at the height of his melodic powers.

For You, for Me, for Evermore

Manuscripts left behind by Gershwin were explored for possibilities, and in 1947 a new motion picture, The Shocking Miss Pilgrim with Betty Grable, offered a “new” and posthumous score, with lyrics, by the irreplaceable Ira. Several of the songs became popular, the most lasting of them being “For You, for Me, for Evermore.”

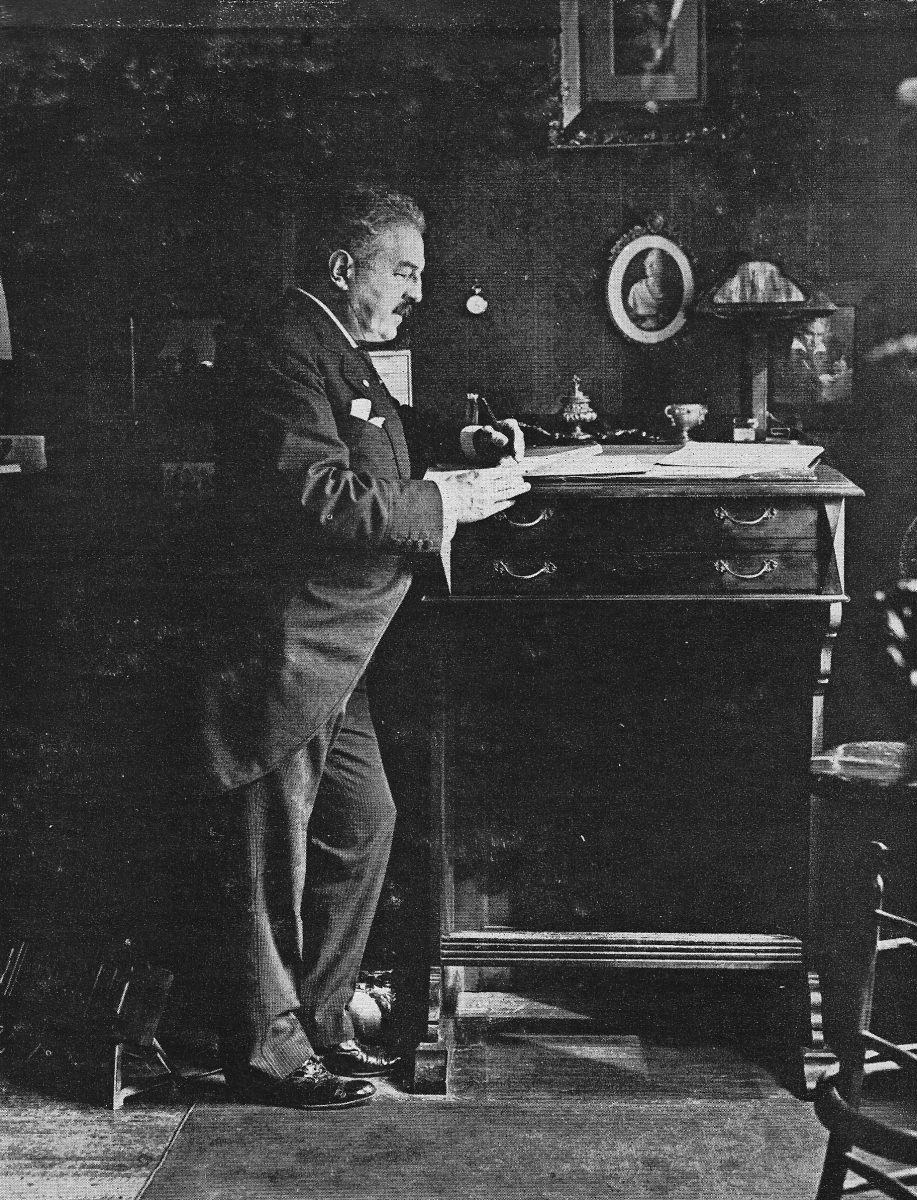

He was something of a giant, Victor Herbert. A big, big-hearted man who wrote big-hearted melodies, he strode across American popular music for some twenty-five years, leaving behind him waltzes, marches and polkas that preserve in their innocent appeal the innocence of those years. He has been called the father of American music, but this is not true, for he was Irish born and German trained. Bit he was the first composer truly oriented toward the tastes of the United States.

Before him, American operetta—the major source of lasting popular music at that time—was largely without character in either music or plot; after him, regardless of what may be said about much of it, there was his legacy of honest sentiment and genuine musicianship. It must have been a proud feeling for Americans of his time to go to a Herbert presentation. Theretofore almost everything worthy of note had come from Europe: the brisk madness of Gilbert and Sullivan, the Viennese confections of Lehar and Oscar Straus, and before them the incomparable Strauss family of Johann jr., Josef, and Johann sr., and the French bonbons of Planquette derived from the frothier gaîtés of Offenbach. And then came Victor Herbert, with Naughty Marietta and Mlle Modiste, The Red Mill and Babes in Toyland, Sweethearts and The Fortune Teller. After that, it was never quite the same in the musical theater. The way had been paved for Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and the others who have made American musicals a vibrant form of art.

Before him, American operetta—the major source of lasting popular music at that time—was largely without character in either music or plot; after him, regardless of what may be said about much of it, there was his legacy of honest sentiment and genuine musicianship. It must have been a proud feeling for Americans of his time to go to a Herbert presentation. Theretofore almost everything worthy of note had come from Europe: the brisk madness of Gilbert and Sullivan, the Viennese confections of Lehar and Oscar Straus, and before them the incomparable Strauss family of Johann jr., Josef, and Johann sr., and the French bonbons of Planquette derived from the frothier gaîtés of Offenbach. And then came Victor Herbert, with Naughty Marietta and Mlle Modiste, The Red Mill and Babes in Toyland, Sweethearts and The Fortune Teller. After that, it was never quite the same in the musical theater. The way had been paved for Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and the others who have made American musicals a vibrant form of art.

In many ways, the music of Victor Herbert reflects the times in which he lived, times which today seem sunny with ease and elegance and confidence (however trying they may have been to those who lived through them). Those were the days of Rector’s and Luchow’s, of driving to the theater in horse-drawn carriages, of suppers of champagne and lobster and cold chicken, of top hats and opera capes, tiaras and sweeping gowns. Not everyone lived that way, of course, but it is agreeable to think of those times in a kind of Gibson Girl setting and not, where Herbert is concerned, without accuracy. Opera stars, such as Emma Trentini and Fritzi Scheff, appeared in Herbert’s operettas, foreshadowing the Metropolitan-to-Broadway moves of later artists such as Ezio Pinza, Helen Traubel and Robert Weede, and if the librettos were more than usually simpleminded, no one seemed to care in the freshet of charming melodies. (One of Herbert’s works, The Gold Bug, lists in its cast of characters such uninviting personalities as Lotta Bonds, Lingard Long, Penn Holder and Lady Patty Larceny, but the composer cannot be held responsible.)

This generous survey of the music of Victor Herbert, arranged and conducted by Percy Faith, draws mainly from his operettas—of which there were forty-two in various guises. There are selections, too, from his grand opera Natoma, from his serenades and from his piano music, melodies that have later become popular in other forms. Herbert is so well known as a composer for the popular theater that it is often forgotten that he composed two operas that reached the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House, a cello concerto of considerable merit, and a large body of piano music, art songs and other works. He was, moreover, conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra for six seasons, was the first composer in America to compose a score for a motion picture (the silent movie The Fall of a Nation) and was of course the major force in the establishment of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers.

Victor Herbert was born February 1, 1859, in Dublin, Ireland. His was a musical family, and as a child he absorbed the musical traditions to which he devoted his life. Some years after his father’s death, his mother remarried and moved to Stuttgart, Germany, where Herbert spent most of his formative years. He began to study the cello early, and in time became a celebrated virtuoso on this instrument. As a youth in Central Europe, he played in many orchestras, as a member of the ensemble and as a soloist, and among those under whom he played was Eduard Strauss, brother of the celebrated Johann.

He also began to compose, and his earliest known work is the Suite for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 3, of 1883. The fate of both Opus 1 and Opus 2 remains a mystery. In 1885, he met the well-known soprano Therese Förster, and after a swift courtship they were married the following year. Shortly after their marriage, they were both summoned to New York by the then youthful Metropolitan Opera Association, she as a dramatic soprano, he as cellist, and moved to America in the autumn of 1886. Mrs. Herbert made her Metropolitan debut as The Queen of Sheba and her second appearance in the Metropolitan premiere of Aida. Although she was well received, she sang only a few more seasons of opera, retiring to devote herself to her family.

Herbert himself, meanwhile, adapted to New York with gusto, making friends with such luminaries as James Huneker, Anton Seidl and Xaver Scharwenka and finding excellent companionship in the eminently respectable beer halls of that era. He made his American debut as a soloist on January 8, 1887, with Walter Damrosch conducting, in portions of his own Suite. Later he played with the New York Philharmonic, and in subsequent years organized his own orchestra for extensive tours and concerts. An idea of his stature as a cellist may be gained from the fact that he played the American premiere of Brahms’ Double Concerto under Theodore Thomas, with Max Bendix as violinist.

Despite all these activities, however, he continued to compose, and made his initial move toward the theater with a dramatic cantata, The Captive, in 1891. His first work for the lyric theater was something called La Vivandière; no one knows quite what it was, for it was never produced and has been entirely lost. In 1893 he began a career as a bandmaster and threatened to rival Sousa, but returned to the theater with a comic opera, Prince Ananias, first performed on November 20, 1894. This was followed by a more notable success, The Wizard of the Nile in 1895, and the following year by his single dismal failure, The Gold Bug, employing the characters cited earlier.

Then in 1897 he had his first unquestioned success, The Serenade, paving the way for The Idol’s Eye and The Fortune Teller the year after. In that same year—1898—he was appointed conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, and remained for six stormy seasons, musical politics being what they are. In 1899 he composed for operettas—Cyrano de Bergerac, The Singing Girl, The Ameer and The Viceroy. His symphonic poem Hero and Leander, Op. 33, appeared in 1901, and in 1903 began the endless procession of memorable operettas—Babes in Toyland, Babette, It Happened in Nordland, Miss Dolly Dollars, Mlle Modiste, The Red Mill, Naughty Marietta, Sweethearts, The Only Girl, Princess Pat, Eileen, Orange Blossoms and Dream Girl—some forty-two in all Moreover, he found time to contribute songs for interpolation in other productions, such as the various Ziegfeld Follies.

In 1911, his grand opera Natoma was produced with Mary Garden and John McCormack. It had been commissioned in 1909 by Oscar Hammerstein, but the loss of his Manhattan Opera House forced the producer to relinquish the rights. The opera was rehearsed in Chicago and Philadelphia before the premiere, and was excellently mounted, but reactions were mixed. Most of the critical fire centered on the book, but there was also a feeling that Herbert had perhaps overreached himself. Nevertheless, excerpts from the work are popular to this day. His other operatic venture, in one act, was Madeleine, produced on January 24, 1914, with Frances Alda. During this time, also, Herbert’s interest in forming a society to protect the rights of composers caught fire, and with eight others, he took the lead in the formation of ASCAP, of which he was director and vice president until his death.

In 1916, he became the first American composer to score a full-length motion picture, The Fall of a Nation, an indifferent film but the first for which a wholly originally accompaniment had been written. That same year he collaborated with an unlikely associate, the young Irving Berlin. The score they turned out was for The Century Girl, and extravaganza for which Herbert wrote most of the instrumental music and some of the songs. With changing tastes in theatrical entertainment, not a few of the Herbert shows of this era were only modest successes. This is surely less his fault than that of the men who compiled the jokes to piece out the time between melodies, but it is also clear that the days of operetta as Herbert knew it were numbered. Still, there was Eileen to come, and Orange Blossoms and The Dream Girl, as well as the celebrated “jazz” concert by Paul Whiteman at Aeolian Hall, for which Herbert composed his A Suite of Serenades. That the Suite was overshadowed by the premier of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on the same program was perhaps to be expected, but the music is nevertheless brimming with the familiar Herbert warmth and charm.

Victor Herbert died on May 26, 1924, collapsing during a visit to his doctor. In a eulogy printed two days later, Deems Taylor wrote: “He is not dead, of course. The composed of Babes in Toyland, The Fortune Teller, The Red Mill, Nordland and Mlle Modiste cannot be held as dead by a world so heavily in his debt.”

The Columbia Album of Victor Herbert, arranged and conducted by Percy Faith, includes the following numbers:

AH! SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE from Naughty Marietta (1910). The final song of the production, it was introduced by Orville Harrold, and has become perhaps the best-known song Victor Herbert ever wrote.

AH! SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE from Naughty Marietta (1910). The final song of the production, it was introduced by Orville Harrold, and has become perhaps the best-known song Victor Herbert ever wrote.

SPANISH SERENADE (1924) is derived from A Suite of Serenades, written for Paul Whiteman and his orchestra and introduced at the famous Aeolian Hall concert that also introduced George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.

DREAM GIRL from The Dream Girl (1924), Herbert’s last operetta. Fay Bainter was starred as the heroine.

BECAUSE YOU’RE YOU from The Red Mill (1906) starring Montgomery and Stone. The original production ran for 274 performances, and a 1945 revival in which Fred Stone’s daughters participated—one as a producer, the other as a performer—ran for 531 performances.

TOYLAND and MARCH OF THE TOYS from Babes in Toyland (1903) an extravaganza intended to duplicate the success of The Wizard of Oz.

GYPSY LOVE SONG and ROMANY LIFE from The Fortune Teller (1898). The first song was introduced by Eugene Cowles. Alice Nielsen was the star of the production.

A KISS IN THE DARK from Orange Blossoms (1922). Edith Day introduced this song, one of Herbert’s finest.

I WANT WHAT I WANT WHEN I WANT IT from Mlle Modiste (1905). Fritzi Scheff was the star of the production, having deserted opera for Herbert’s earlier Babette. This number was not hers, however; it was sung by William Pruette.

WHEN YOU’RE AWAY from The Only Girl (1914) was introduced by Wilda Bennett. One of Herbert’s most successful works, The Only Girl followed the opening of The Debutante by only five weeks.

CUBAN SERENADE is also from A Suite of Serenades written for Paul Whiteman in 1924.

INDIAN SUMMER was originally composed for piano in 1919. It was later orchestrated, and some twenty years later was adapted as a popular song with unusual success.

EVERY DAY IS LADIES’ DAY WITH ME from The Red Mill (1906). It was introduced by Neal McCay as the Governor of Zeeland.

KISS ME AGAIN from Mlle Modiste (1905). This was Fritzi Scheff’s greatest success, part of a number called “If I Were on the Stage.” Legend—fairly well substantiated—indicates that she originally detested the song, and that it remained in the production only at Herbert’s insistence.

HABANERA from Natoma (1911). Herbert’s grand opera was produced with a cast headed by Marty Garden and John McCormack. Burdened by a soggy libretto, it nevertheless contained many memorable moments, among them this richly atmospheric selection.

TO THE LAND OF MY OWN ROMANCE from Sweethearts (1913). Christie MacDonald was the star of the production, which ran for 136 performances. A revival in 1947 achieved 288 performances.

DAGGER DANCE from Natoma (1911) is yet another atmospheric excerpt from Herbert’s grand opera, building to a dramatic climax. The opera remained in repertory for three seasons, something of a disappointment to its well-wishers but a distinguished effort in American opera of its time.

ITALIAN STREET SONG from Naughty Marietta (1910) was a showpiece for Emma Trentini of Oscar Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera Company. She, and the score, helped make the production a classic of the operetta stage.

SWEETHEARTS from Sweethearts (1913) is a typically Herbertian waltz, and one of the most popular he ever wrote.

YESTERTHOUGHTS (1900) was composed for piano, later orchestrated and, like Indian Summer, transformed into a major popular song in the late Thirties.

STREETS OF NEW YORK from The Red Mill (1906) demonstrates another type of Herbert waltz—light-hearted, rollicking and tuneful as always.

I’M FALLING IN LOVE WITH SOMEONE from Naughty Marietta (1910). Orville Harrold, of the Manhattan Opera Company, introduced this song, one of the high spots of Herbert’s finest score.

THINE ALONE from Eileen (1917). This production was Herbert’s heartfelt tribute to the land of his birth, one of his loveliest scores and a curiously neglected one. Its most famous excerpt, presented here, was introduced by Walter Scanlan and Grace Breen.

THE YEAR WAS 1960. Elvis Presley was out of the army and "Stuck on You," Chubby Checker was busy doing "The Twist," Bobby Darin was dreaming of his lover "Beyond the Sea," and Brian Hyland was making sure everyone saw that "Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini." Yet in the year-end Top 40 filled with memorable pop and rock-and-roll melodies of every stripe, one stood head and shoulders above the rest. Resplendent violins, warm brass and lilting piano triplets took Percy Faith's "Theme From A Summer Place" to the Billboard Hot 100's No. l spot on February 22, 1960. The atmospheric ballad stayed there for nine consecutive weeks, a record which wouldn't be tied until 1968 with The Beatles' "Hey Jude" and wouldn't be broken until 1977 thanks to Debby Boone's "You Light Up My Life." Today, Faith's Grammy Award-winning Record of the Year remains the longest running instrumental No. 1 in the history of the Hot 100, and one of the most recognizable pieces of music of all time, cropping up with regularity on film and television. For all its success, "Theme from A Summer Place" is just one essential part of the remarkable musical legacy of Percy Faith. The late artist's innovative orchestration techniques placed him at the vanguard of the lush genre known alternatively as mood music, light music, or beautiful music. Real Gone Music's The Definitive Collection is a widescreen portrait of his most sweepingly romantic themes for young lovers and beyond.

"Percy Faith was very, very instrumental in my career," Johnny Mathis confided to this author in a 2015 interview. "I was thrilled to be able to work with Percy." Johnny is just one of the legendary artists who benefitted from Faith's musical acumen, collaborating on such acclaimed albums as Good Night, Dear Lord and the bestselling Merry Christmas. Tony Bennett recalled to Variety last year of Faith's golden touch: "I was a jazz singer. And Mitch Miller said, 'Don't do that.' So they gave me Percy Faith and his orchestra, and my first record was 'Because of You' in 1951, which was No. 1 for ten weeks." As Mathis revealed, "Percy was an artist-in-residence at Columbia Records who had no obligation at all to do anything other than record his own music. It was a kindness on his part [to record with me]." That kindness, and his abundant skill, established Faith as an in-demand personage for more than 25 years at the label. He arranged and conducted over 75 of his own albums as well as hundreds of sides for the cream of the Columbia crop.

Born on April 7, 1908 to a working class family in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Faith was inspired by his uncle, a violinist, to take up music at the age of seven. Piano came naturally to the young man, and by eleven, he was performing in public. At fifteen, he gave his concert debut at Toronto's venerable Massey Hall, but at eighteen, his promising future in music was nearly curtailed. Faith and his three-year-old sister were at home when her clothing caught on fire. Stamping out the flames with his hands, he saved his sibling's life, but the injuries left him unable to continue as a classical pianist. He resolved to use his gifts elsewhere in the musical realm, and turned to arranging and conducting.

Beginning in the early 1930s, Faith became a fixture on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's radio programming. In 1937, he launched his own CBC show, Music by Faith, and before long it was picked up to air in the United States as well. In 1940, Faith headed to the U.S. and took the reins of The Carnation Contented Hour in Chicago. Moving to New York and continuing his upward trajectory, he began an association with the NBC network, and then with CBS. Late Late in the decade, he began recording for various labels including Majestic, RCA Victor, and Decca, where he was employed in the field of A&R (Artists and Repertoire). Faith’s early recordings set the tone and style for the rest of his career. On September 20, 1947, Billboard reviewed The Exciting Music of Percy Faith, a Majestic album of 78s: "Scoring a set of six familiars screen and stage songs with rich instrumental color in the harmonies of the strings and woodwinds, to which is blended symphonic overtones and a pronounced rhythmic beat, maestro Percy Faith provides easy and pleasant listening for those desiring the everlasting song favorites in full instrumental dress." The glowing review could have just as accurately described his recordings in the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s.

Columbia Records took notice of Faith’s exquisite sound. In 1950, Percy joined the label as both a recording artist and musical director working closely with A&R chief Mitch Miller. (In addition to the tracks which he produced for Faith, Miller can be heard on "Music Until Midnight (Lullaby for Adults Only)" playing English horn and oboe.) In a busy first year, Faith accompanied vocalists including Rosemary Clooney, Tony Bennett, and Frank Sinatra while cutting his own singles. The August release of "All My Love (Bolero)" established him as a major presence. His recording featuring The Ray Charles Singers reached No. 7 on the Billboard chart despite stiff competition from other versions of the same song by the orchestras of Xavier Cugat and Guy Lombardo, Bing Crosby, and Patti Page. Patti's rendition ultimately eclipsed the others by reaching No.1.

The bolero beat of "All My Love" is just one illustration of Faith's frequent application of Latin forms to his music. His 1947 Decca album Fiesta Time was praised by Billboard for "creating a carnival spirit in the varied and contrasting moods and rhythms, taking in the samba, guaracha, bolero, and tango dance forms." When he joined Columbia, he mined the rich veins of Latin and South American music on tracks such as "Jungle Fantasy" by Puerto Rico's Esy Morales and "Delicado" by Brazil's Valdir Azevedo. Prominently spotlighting Stan Freeman on a vibrant harpsichord, "Delicado" gave Percy one of his most enduring hits when it peaked at No.1 on Billboard in 1952. It would be his first chart-topper but not his last.

Faith's recording of "Where is Your Heart" from the film Moulin Rouge was crowned the top song of 1953. The ballad by French composer Georges Auric with American lyrics by William Engvick was a vocal number credited to "Percy Faith and His Orchestra featuring Felicia Sanders." The single lasted an impressive 24 weeks on the chart, residing at pole position for ten of those weeks. Faith continued to work with Sanders through 1956 on her solo recordings, but none matched the success of the alluring, ethereal movie theme.

Indeed, the music of Hollywood plays a central role in the Percy Faith story, and he recorded several LPs of memorable movie themes. The Definitive Collection includes a number of his cinematic excursions, including Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington's shimmering "Return to Paradise" from the movie of the same name, the rousing "The Bandit (Theme from O Cangaceiro)" from the Brazilian western, Luis Bonfá's and Antonio Maria's "Samba de Orfeu" from Black Orpheus, Nino Rota's "Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet" (for which Faith picked up his second Grammy), and Jerry Goldsmith's "Theme from Chinatown" from the Academy Award-nominated score.

An accomplished melodist in his own right, Faith scored a number of motion pictures. In a 1970s radio interview with disk jockey and perennial game show host Wink Martindale, Faith revealed that Warner Bros. Records had actively courted him in 1959 to leave Columbia. Among the enticements was entree to the WB film studio as a composer. Faith believed that, had he accepted the offer, one of the WB pictures he could have scored was none other than A Summer Place. He couldn't have known at the time that his name would become more associated with the film than its composer, Max Steiner.

A friend in the publishing business who had previously tipped Faith to "Delicado" brought him a cue from Steiner's score. Faith immediately recognized the composition's pop potential: "It had the beginning, the semblance of what was going on [in popular music]… I could hear a new type of drumming. There was something going on. It was the beginning of rock, which was coming out of R&B music." Faith was surprised that the theme had come from the veteran Steiner's pen. He immediately phoned the composer, who was twenty years his senior. Percy remembered Steiner telling him, "I played the melody which was in 4 [to the publisher], and the dirty little so-and-so turned it into a 6/8, and put these triplets in and was trying to tell me it was something new! Hell, Beethoven and Mozart have been using triplets for 200 years!"

Of Faith's own film work, most notable is The Oscar (1966). The drama co-written by science-fiction great Harlan Ellison marked Tony Bennett's silver screen debut, and yielded a Top 10 Easy Listening hit for the singer with Faith, Jay Livingston, and Ray Evans' "Song from The Oscar (Maybe September)." The Definitive Collection additionally presents the movie's "The Glass Mountain" as well as Faith and Mack David's "The Love Goddess" from 1964's The Love Goddesses, and "Tammy Tell Me True" from the comedy of the same name that Faith scored in 1961. "The Virginian," his theme to the 1962 NBC western series, could be heard Wednesday nights on the network for the program's first eight seasons. (Faith's recording of "The Syncopated Clock" from "Sleigh Ride" author Leroy Anderson was also familiar to television viewers as the theme to CBS-TV's The Late Show movie between 1951 and 1976.)

Like Hollywood, Broadway beckoned Faith. Over the years, more than ten musicals got the album-length Percy Faith treatment at Columbia, from Kismet (1954) through Jesus Christ Superstar (l971). Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe's jubilant showstopper "With a Little Bit of Luck" and courtly "Embassy Waltz" have been culled from Percy's 1956 recording of My Fair Lady (the original production of which was bankrolled by Columbia). A bucolic reading of the same songwriters' "Camelot" hails from his 1960 album dedicated to the musical. The LP was promoted by the label alongside the Original Broadway Cast Recording and another "cover" album from Andre Previn's trio.

Along with Latin and movie music, pop was another key component of the artist's oeuvre. The dawn of the 1960s saw him relocate from New York to California, and concentrate more heavily on his own recordings rather than as an arranger-conductor for the label's singers. So successful was he that Columbia deemed October 1960 to be "Percy Faith Month," pushing his 27 releases to that point by servicing record stores with special racks, brochures, photos and more.

As the sound of American popular music changed, so did Percy Faith. The Definitive Collection showcases a pair of 1950s now-standards written by lyricist Carl Sigman, "Ebb Tide" and "Till." Percy introduced the latter, originally written in French, but Pianist Roger Williams had the more successful recording, reaching No. 22 to Percy's No. 63 on the Billboard survey. Faith composed the relaxed "Theme for Young Lovers" as a 1960 single, peaking within the Top 40. Three years later, he re-recorded the song as the title track of Themes for Young Lovers. The album introduced the "new" Percy Faith, interpreter of contemporary pop-rock hits in soft yet imaginative arrangements. It included future classics from Carole King and Gerry Coffin, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, and Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, and became Faith's most successful non-holiday long-player. Themes for Young Lovers reached No. 12 on the Billboard Top LPs (Stereo) countdown and became his longest-charting album, at 36 weeks. (Camelot was runner-up, at 23 weeks.)

Naturally, Columbia wanted more of the same. Soon, Percy was adapting Great Folk Themes into instrumental form, and selecting Latin Themes for Young Lovers (Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius De Moraes and Norman Gimbel's beguiling "How Insensitive") and Themes for the "In" Crowd (Billy Page's "The ‘In’ Crowd," a hit for both The Ramsey Lewis Trio and Dobie Gray). New standards by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Jimmy Webb, Paul Simon, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney filled Faith's albums. Between 1963 and 1976, the ever-prolific Faith released more than 25 albums of pop hits, often named for those songs: Leaving on a Jet Plane, I Think I Love You, Black Magic Woman, and Clair among them. As of the mid-sixties, Columbia also urged Faith to incorporate a chorus into most of his recordings. He had intermittently employed vocalists on his records since his earliest days at the label, but voices took on a new prominence within his instrumental textures during the lyric-oriented rock era.

Percy Faith never stopped looking forward. He told historian Gene Lees in 1974, "It's an electronic world now, and I've been studying the Moog, the Arp, the Fender Rhodes piano. I use them in my recordings sometimes." After having revisited "Theme from A Summer Place" in a vocal version in 1969, he returned to it once more in September 1975 as "A Summer Place '76." The updated track retained the original's soaring strings and added a joyous disco beat, yielding a No.13 Easy Listening hit.

On February 9, 1976, Percy Faith died of cancer at the age of 67. Forty years have passed since his death, yet the popularity of his music has hardly waned. Most of the albums in his massive Columbia discography remain in print today, and his timeless sets of Christmas music are revived year after year as true staples of the genre. His influential arrangements live on, too, via concert performances and re-recordings by respected conductors such as Alan Broadbent, Terry Woodson, and the late Nick Perito.

"I loved Percy Faith," Johnny Mathis said, "because I think he was the most inventive of all with his sound." The deceptively simple style of Percy Faith can't be summed up in a single word, though many certainly apply: sophisticated, romantic, whimsical, dreamy, relaxing… just don't call it elevator music!

In Percy's handwriting:

The orchestra and I enjoyed the experience of recording this concert "live" at Kosei Nenkin Hall in Tokyo on May 19, 1974.

Percy Faith